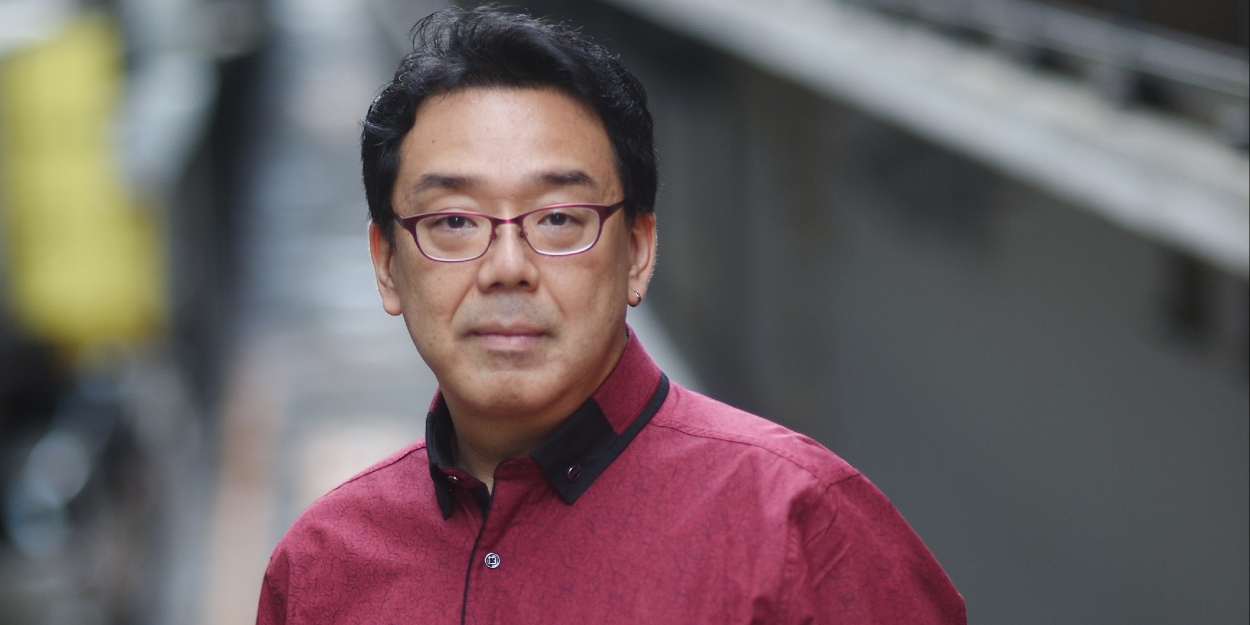

Interview: Hiro Iida, an Electronic Music Designer Making Waves Worldwide

A sound craftsman who convinces all kinds of professionals on Broadway.

Hiro Iida: Known as an electronic music designer making waves worldwide, he's a sound craftsman designing the sound of musicals. A graduate of Berklee College of Music, he has won two Grammy Awards. Some of his notable works include "The Notebook THE MUSICAL," "THE GREAT GATSBY," "Kimberly Akimbo," "Tootsie" on Broadway, "MJ THE MUSICAL," "Mean Girls" in the UK, "The Man Who Laughs," "Mata Hari," and "XCALIBUR" in Korea, as well as "DEATH NOTE THE MUSICAL," "Musical IKIRU," and "musical Your Lie in April" in Japan. He has also provided music to notable figures like Akiko Yano.

What were you like before coming to the States?

I was a student at a public high school, with a focus on music activities. I've been fascinated with synthesizers since I was eight, but at that time, making music with synthesizers was still like a distant dream.

I was planning to go to a university in Japan, but I wanted to study synthesizers. There still isn't a place in Japan where you can study synthesizers at a university level as an academic subject from the 1980s to the present. When I thought about studying electronic music for four years at a university, my only option was to study abroad. So in 1985, I went to Berklee College of Music in Boston.

Did you already have a plan to stay in the States afterwards?

There were no people around me who were studying abroad in high school, and I didn't know anyone there at the time, so I set a five goals, "I'm going to the States from now on!"

My first goal was to graduate with a four-year degree. The second was to legally work in the States with the degree I studied. The third was to be able to live 100% on that. The fourth was to be recognized or increase my popularity by continuing to do that. And the last one was to be able to live on my legacy even if I quit my job.

So, when I graduated from college, I had this step in mind: living in the States in that field, achieving Tony Awards and Grammy Awards along the way, and ultimately being able to live without doing anything. That's why from the moment I went there, I had a strong consciousness of wanting to pursue my career globally in the States.

Are you on an artist visa now?

I started with a student visa. Then when I got a job at Berklee, I got a work visa and taught there for six years. I was able to get an artist green card by contributing to higher education in the States and doing artistic activities using synthesizers.

How did you end up teaching at school?

After graduating from Berklee, I actually wanted to study more academically about psychoacoustics and sound design at Stanford University's CCRMA (Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics) or MIT's Media Lab.

But when I was thinking about graduate school, Berklee offered me a job to teach after graduation. So I was torn between taking academics or teaching at Berklee, which is more on the jazz and pop side and closer to the entertainment music field, and I chose to stay at Berklee and become a teacher, starting from being a teaching assistant.

Then you were invited to work on the “Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark,” correct?

Skipping ahead a bit, I actually left Berklee in '97 because I got my artist green card, so I didn't need to work at Berklee anymore. Then I moved to New York.

I actually hated musicals at the time. Musicals like "Cats" were playing, but every time I passed by the theater, I would curse at them because I thought they suddenly started singing so obviously.

At that time, Japanese artists were still coming to New York for recording, and overseas recording was still frequent. I understood English and engineering, and I could play the keyboard, so I started working as a freelance director and such. I also started writing music for the American TV shows and commercials. The first ten years in New York were completely unrelated to musicals.

But one day, in a Japanese community in New York, someone said to me, "Japanese people can't work unless they're connected with Japanese people!" I thought, "That's bullshit!" and that's when I decided that as long as I'm in New York, I won't work with Japanese clients except for Akiko Yano whom I knew well back then.

From there, one of the jobs I picked was WWE (World Wrestling Entertainment) in the States. Pro wrestling is similar to musicals in terms of production because everything, including the script and choreography, is predetermined. Otherwise, they'd get injured. I worked on theme songs, entrance and exit music, music for DVDs, movies, games, and sound effects for about three to four years.

Then I was invited to work as a keyboard programmer for U2. WWE was a good company, but when I quit for the chance to work with U2, it turned out to be Spider-Man the musical.

Was the person who offered you the job someone you knew from wrestling?

No, he was involved in musicals like Jekyll & Hyde and later to be my business partner, Billy Stein. He asked me if I could help out based on hearsay.

When creating Spider-Man, director Julie Taymor and the production team expressed a desire for something entirely new, bringing in external individuals who hadn't worked on Broadway before. So there were also teams from Cirque du Soleil, the Spider-Man movie team, and costume designer Eiko Ishioka.

Until then, in musicals, people had just bought existing synthesizers and selected sounds to play, but that meant that when new products came out every five years or so and the old ones were discontinued, you couldn't buy them anymore.

For Spider-Man, they wanted a system where even if you replaced the computers every 10 to 20 years, the same sound would continue to be produced without changing any data, maintaining the exact same state indefinitely.

I was asked to create this for the first time in commercial theater worldwide. Using my connections from Berklee, I brought companies like Roland and Apple into the live entertainment world and collaborated to develop instruments and software together. That's how I entered the world of musicals.

From disliking musicals to entering that world with Spider-Man, what made you continue with that work?

After that, word spread that the system for Spider-Man was amazing, and work started coming in. One of them was SHREK THE MUSICAL, and I also participated in the national tour. It was about my third year since I started working in musicals, but at that time, I was still doing it just for the good money without really knowing what was interesting about it.

During the rehearsals for SHREK, we were in Yakima, Washington, a rural town where there was a decent theater but restaurants and cafes closed around 2 p.m. Despite that, all the staff gathered there and rented the theater for a month for rehearsals. When we needed audience reactions, we sold tickets for $5 or so to locals to come and watch.

But the audience in Yakima hadn't seen a musical before, so they didn't have theater etiquette. They ate and drank, asking, "What's that scene about?" and making a lot of noise. However, the fun part was that they laughed uproariously, cried during sad moments, and got angry together. The range of emotions was unlike New York audiences; it was their first time, so it was different.

So, supporting a musical with my own created sounds and music, and capturing the emotions of a thousand audience members, making them laugh and cry, made me realize, "I'm actually doing something incredibly exciting." It felt like magic for the first time, and I wanted to commit to it more. It's all thanks to the audience in Yakima.

What is the most challenging aspect of your work, and how do you overcome it?

There are several, but there's a difference between "hard" and "difficult." In terms of difficulty, Asian discrimination can't be avoided.

Right now, among the production teams of the 41 Broadway theaters, Asian male members make up only 0.6%. So when I go to a theater for the first time, I'm stopped by security at the stage door and asked, "What are you here for?" I had to deal with that kind of difficulty at first.

For example, when I entered the theater for "THE GREAT GATSBY" two days ago, it was the first time for me, so I tried to befriend the security guard. I introduced myself and said, "I'm going to Starbucks, do you want anything?" If there's no way to argue, you have to show them that "we're colleagues making a musical" and overcome it.

The hard part of creating is that a musical is not just about music; it includes acting, lighting, sound, set design, stage management, production, direction... They're all subjects taught at American universities. Japan is probably the only developed country where theater is not taught at national universities, so almost everyone working on Broadway has a degree in their field. I have to create the right sound for that and convince all the professionals in those fields.

For example, when I was asked to create a "time slip" sound for "MJ THE MUSICAL," about 100 specialists in each field had to be convinced. And it's not just a matter of “It's okay” but it has to be like, "Wow!" So I often say, "overwhelm with sound." Not just asking, "What do you think about this?" but saying, “How’s this!" That's the only way to overcome it, though it's hard, it's interesting.

What do you think are the good and improvable aspects of Japan's entertainment industry?

In the Broadway scene, everyone is protected by the labor union they belong to. If you're not a member of the union for audio, lighting or anything, you can't enter the scene. On the other hand, there are many restrictions due to the union, and if you don't follow the rules, you can't work. For example, if you're told to take a lunch break, you can't work during lunchtime.

Japan is very free and flexible because there is no union, but it's also very exploitative in a negative sense.

When I worked on "MJ THE MUSICAL" in London, there was no union, but workers were still protected, striking a good balance. There wasn't the rigidity of having to take lunch breaks just because it was lunchtime. If someone wanted to work while others took lunch, they could do so and take their break later. There wasn't the kind of pressure you find in Japan where you have to work while secretly eating snacks.

While the organized structure in the States is good, I don't necessarily think that importing the union system as it is would be the solution for Japan.

Could you tell me more about "big, fun projects" you aim for?

It's not that difficult to create the same sound. For example, when someone says, "I want this kind of sound," sometimes you have to create sounds that no one has ever heard before from scratch. The harder it is, the more enjoyable it becomes.

Gathering sounds from the existing palette, asking, "Isn't this sound good enough?" may make the process easier if that works, but it's not very exciting. For those kinds of projects, I tend to feel like, "I don't need to come and see it until it's open," or "I'll leave it to the assistant and move on to the next thing," and I end up getting bored myself.

On the other hand, there are projects like MJ where you create everything from scratch. In the recently opened "The Notebook THE MUSICAL," the composer had a strong attachment to the sound of just one piano. I wonder how many versions I made of it, thinking, "Not like this, not like that." Creating those was fun. It gives me a sense of accomplishment.

Finally, could you give a message to those aiming to be artists abroad like yourself?

Outside of Japan's insular culture, it's a jungle where only the strong survive. Having a loud voice doesn't necessarily mean you'll win or that you're right, but in terms of artistry, it's essential to create something with 140% of your effort that says, "I won't take any complaints!"

Even if nobody acknowledges you, if you have something in yourself that you can be proud of in the world, the world outside of Japan is incredibly enjoyable. I want you to challenge yourself to find that and go out into the world.

Just like how Japanese people won an Academy Award this year, they probably thought, "This is where we're the best in the world," and that's why they were able to succeed. I think it's most important to nurture and hold onto that within yourself.

Photo Credit : [Kunihiko Takaoka]

Comments

Videos