Cindy Marcolina - Page 2

Italian export. Member of the Critics' Circle (Drama). Also a script reader and huge supporter of new work. Twitter: @Cindy_Marcolina

September 13, 2024

The Seventies were a time for cheesy pineapple, bellbottom jeans, Elton John, and ABBA. Written in 1977, Mike Leigh’s darkly comic picture of the English middle class turns out to be an evergreen classic. Revived some ten miles from the story’s real-life setting, this is Nadia Fall’s last show as Artistic Director of the venue and features known ‘EastEnder’ Tamzin Outhwaite as Beverly Moss.

September 10, 2024

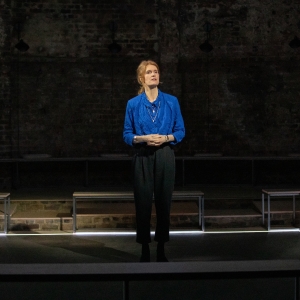

Leigh’s husband was arrested for inappropriate sexual conduct with a minor. A teacher once loved by students and parents alike, he’s now out of prison and facing the casualties of his violent fall from grace. Playwright Carey Crim explores the effects of these serious allegations on the ones who surround the accused, viewing the aftermath of the crime mostly from Tom’s family. As Leigh tries her best to protect their son and stand by her spouse, her faith in him falters. Is he really capable of what he’s been charged with? Far from an easy watch, this is a thought-provoking and provocative piece of theatre.

September 6, 2024

Having to move back with your parents after a failed marriage is raising all types of questions that Larki can’t or doesn’t want to answer. Aunties and fake friends are all up in her business while her life is crumbling around her. Saher Shah’s playwriting debut is a bittersweet look into individual reinvention and the disappointment that comes with certain social conventions.

September 9, 2024

The Irish writer Brendan Behan described critics as “eunuchs in a harem; they know how it’s done, they’ve seen it done every day, but they’re unable to do it themselves”. Quite a damning characterisation. Anand Tucker introduces an ageing critic, Jimmy Erskine, whose name and ruthlessness are the stuff of legends. When a struggling actress becomes entangled in his web, Erskine drags both of them down a dangerous path. Loosely based on Anthony Quinn’s novel Curtain Call but featuring a different premise, The Critic is a solid, witty black comedy before seamlessly shifting into a chic crime drama.

September 1, 2024

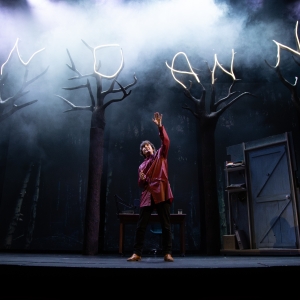

Magical realism is hard to come by in the theatre. Playwright Tife Kusoro dips into urban legends and creepypasta to deliver a fascinating coming-of-age piece. With stunning direction by Monique Touko, G is a brilliant supernatural cautionary tale - a description that’s, admittedly, not entirely accurate nor comprehensive of everything the play is. Kusoro infuses her work with surrealism and harsh socio-political critique, pure banter and sheer terror. It’s young and fresh and ingenuously subversive. It’s a comic thriller, but also an unsettling allegory and a story about the power of friendship and loyalty. Kusoro is definitely onto something.

August 7, 2024

The production embraces Jewish representation and celebrates their religious rituals with refreshing openness. From Tevye’s personal relationship with God to the customs of his culture, there’s pride in Fein’s take. He imbues it with tradition, lifting the narrative to a universal story of love and sacrifice; the outdated strands of ideas end up cementing an emotive snapshot of a past that’s ruthlessly and constantly repeating somewhere. Charming, heart-rending, and utterly gorgeous, this is the revival of Fiddler.

August 6, 2024

In line with the trend of the moment, this is more than a concert and less than a full production. The set has been kept to a minimum, featuring only two heavy-looking wooden tables with chairs and banners with Tudor insignia, but there’s enough costumes and choreography to have a proper glimpse of what it might look like fully staged.

August 3, 2024

The show is in itself show-stopping. The cast of accomplished triple-threats swaps tense competition for a jubilant celebration of form. In a post-pandemic industry that’s suffered cuts to the arts across all areas, it’s disheartening to see an artist’s quality of life hasn’t exactly progressed much. But, gosh, they make it look so beautiful.

August 1, 2024

The piece is heavy in topic and method, but Carrie Cracknell’s quiet direction smooths out the nearly three hours of running time. It’s by any means not an easy-breezy show to experience, but it sinks into your soul in a way that only an epic does. The problem is that it’s so, so slow.

July 20, 2024

It’s haunted by a script that’s as creaky as the house investigated by the characters, but it’s captivating enough here and there. After a fascinating lecture held by Professor Dubois, Erin sets off to find out why people keep disappearing at Torhill Wood.

July 18, 2024

Friends with benefits. Casual lovers. Non-romantic sexual partners. They’re all terms that Google feeds you if you’re trying to define a relationship where one will undoubtedly end up catching feelings. Him and Her are attempting to circumnavigate the exact same situation(ship). She likes that he’s slipping up and imagining a future with her; he somewhat ponders an outcome where they become a family. Neither thinks they want - or are ready for - stability. Siofra Dromgoole writes a series of post-coital scenes that explore the definition of recreational sex and romance.

July 11, 2024

However, penned by Joe Evans (score and lyrics) and Linnie Reedman (book and direction), Dorian is an awkward production that’s supposedly adapting the mores and morals of the time for a social media-obsessed audience. They reimagine the protagonist as a lonely rocker who gains overnight popularity after producer Harry Wotton takes him under his wing. Basil Hallward becomes Baz, a celebrity photographer charmed by the young star, while Sibyl Vane is a besotted opera singer. We wish we could say it works, but the team desecrates the original material - and not in a good way. Sex, drugs, and rock’n’roll have never looked so dull and unappealing.

July 4, 2024

Alma Mater is the byproduct of fourth-wave feminism, with faint echoes of David Mamet’s Oleanna flipped on its head and delivered with a sleight of hand. Polly Findlay is back at the Almeida to direct Kendall Feaver’s world premiere, which finally officially opens after a troubled start. The withdrawal of Lia Williams, who was initially due to take on Jo, doesn’t seem to hinder this unforgiving production, with Justine Mitchell taking over with an assured stance.

July 3, 2024

They say you find love when and where you least expect it, but swearing off relationships isn’t just a contemporary manifestation of ennui. It’s 1943 and typical New York actress Sally has decided to focus on her career rather than chase men who don’t give her the time of day. Her colleague and best friend Olive has a different life plan.

June 26, 2024

Back in 2021, Danny Robins spoke to the void in the shed in his garden asking “Do ghosts exist?”. The world of paranormal podcasts never was the same. People were quick to join in online, sending reports and building a network of experiences, lifting the series to a cult media of sorts. Robins went on to write the astoundingly successful celebrity bait 2:22 A Ghost Story and produce many more seasons of the spooky pod for the BBC before turning them into live shows and serialised television.

June 29, 2024

The production is frankly unnecessary, too long, and way too slow for what it really is. The characters (publicist Pat Newcomb, actor Peter Lawford and his wife Patricia Kennedy, Marilyn’s psychiatrist and his spouse, her physician, and her housekeeper) go around in circles like Masterson’s revolving stage, beating around the bush until, finally, we find out what the core of the issue is, nearly halfway through the second act. They’re all trying to protect the Kennedys: a scandal would bring down the government at a crucial point in history.

June 20, 2024

Laura Waldren lifts the veil off an eating disorder unit. While the characters try hard to cope with an alienating structure that fails many of its patients, Waldren examines institutional callousness and human failure. Chosen from a staggering 1,468 scripts, Some Demon it’s an excellent pick. Though far away from an easy watch, it’s rife with urgent necessity.

June 18, 2024

Written by Stewart Pringle, The Bounds takes punters to 1553, “the true Golden Age of English football”, when matches could last hours or days and rules were, though relaxed, quite severe. While people are playing in the distance, our protagonists of humble Northumbrian origins end up debating a lot more than football. Rife with superstition and mythology, the piece lives in a limbo.

June 14, 2024

The Coronet might be the most internationally inclined venue in London. From hosting Japanese companies to putting on an entire programme of Taiwanese work, they stage remarkable projects. Once the home of the Italian Theatre Festival, the theatre is now presenting a translation of one of Britain’s most prominent authors.

June 13, 2024

Either the immersive industry is floundering, or the craze has passed. Only last year, the most simple in-the-round staging was deemed immersive. These days, we’ve returned to a reduced scene, with only Punchdrunk hitting the news and Phantom Peak continuing its winning streak. Something smaller and more enigmatic has opened in London. Tucked away in a secret location in the heart of Clerkenwell, Vegetables is a wild ride. The production is shrouded in mystery, with the address given only upon booking and its exact plot begged to be kept hush-hush. The gist is that people’s consciousness can now be transferred into everyday veggies to cure all maladies mental and physical; we are the first to witness this new scientific advancement.

Videos